Investigating Human Priors for Playing Video Games

探索人类先验知识在电子游戏中的应用

Rachit Dubey 1 Pulkit Agrawal 1 Deepak Pathak 1 Thomas L. Griffiths 1 Alexei A. Efros 1

Rachit Dubey 1 Pulkit Agrawal 1 Deepak Pathak 1 Thomas L. Griffiths 1 Alexei A. Efros 1

Abstract

摘要

What makes humans so good at solving seemingly complex video games? Unlike computers, humans bring in a great deal of prior knowledge about the world, enabling efficient decision making. This paper investigates the role of human priors for solving video games. Given a sample game, we conduct a series of ablation studies to quantify the importance of various priors on human performance. We do this by modifying the video game environment to systematically mask different types of visual information that could be used by humans as priors. We find that removal of some prior knowledge causes a drastic degradation in the speed with which human players solve the game, e.g. from 2 minutes to over 20 minutes. Furthermore, our results indicate that general priors, such as the importance of objects and visual consistency, are critical for efficient game-play. Videos and the game manipulations are available at https://rach0012. github.io/human RL website/.

是什么让人类在解决看似复杂的视频游戏时如此出色?与计算机不同,人类携带着大量关于世界的先验知识,从而能够高效决策。本文探讨了人类先验知识在解决视频游戏中的作用。给定一个示例游戏,我们进行了一系列消融实验,以量化各种先验对人类表现的重要性。具体方法是通过修改视频游戏环境,系统地屏蔽可能被人类用作先验的不同类型视觉信息。我们发现,移除某些先验知识会导致人类玩家解决游戏的速度急剧下降,例如从2分钟延长至超过20分钟。此外,我们的结果表明,诸如物体重要性和视觉一致性等通用先验对于高效游戏至关重要。视频及游戏操作修改详见 https://rach0012.github.io/human_RL_website/。

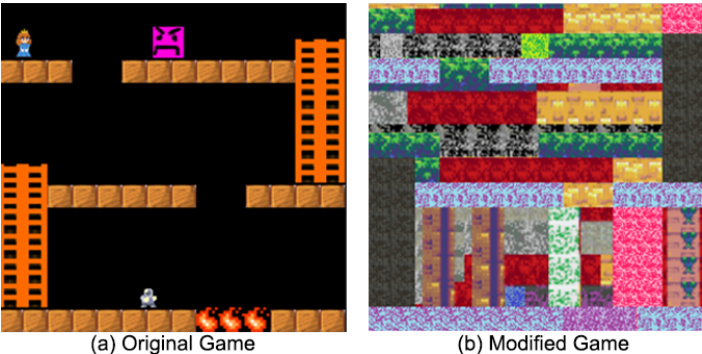

Figure 1. Motivating example. (a) A simple platformer game. (b) The same game modified by re-rendering the textures. Despite the two games being structurally the same, humans took twice as long to finish the second game. In comparison, the performance of an RL agent was approximately the same for the two games.

图 1: 动机示例。(a) 一个简单的平台游戏。(b) 通过重新渲染纹理修改后的同一游戏。尽管两款游戏结构相同,但人类完成第二款游戏的时间是第一款的两倍。相比之下,强化学习智能体 (RL agent) 在两款游戏中的表现大致相同。

ure 1(a). No manual or instructions are provided; you don’t even know which game sprite is controlled by you. Indeed, the only feedback you are ever given is “terminal”, i.e. once you successfully finish the game. Would you be able to finish this game? How long would it take? We recruited forty human subjects to play this game and found that subjects finished it quite easily, taking just under 1 minute of game-play or 3000 action inputs. This is not overly surprising as one could easily guess that the game’s goal is to move the robot sprite towards the princess by stepping on the brick-like objects and using ladders to reach the higher platforms while avoiding the angry pink and the fire objects.

图 1(a): 没有提供任何手册或说明,你甚至不知道哪个游戏精灵由你控制。事实上,你获得的唯一反馈是"终止",即当你成功完成游戏时。你能完成这个游戏吗?需要多久?我们招募了40名人类受试者来玩这个游戏,发现受试者相当轻松地完成了游戏,仅用了不到1分钟的游戏时间或3000次动作输入。这并不特别令人惊讶,因为人们可以轻易猜到游戏的目标是通过踩踏砖块状物体和使用梯子到达更高的平台,同时避开愤怒的粉色物体和火焰物体,将机器人精灵移向公主。

1. Introduction

1. 引言

While deep Reinforcement Learning (RL) methods have shown impressive performance on a variety of video games (Mnih et al., 2015), they remain woefully inefficient compared to human players, taking millions of action inputs to solve even the simplest Atari games. Much research is currently focused on improving sample efficiency of RL algorithms (Gu et al., 2016; Oh et al., 2017). However, there is an orthogonal issue that is often overlooked: RL agents attack each problem tabula rasa, whereas humans come in with a wealth of prior knowledge about the world, from physics to semantics to afford ances.

虽然深度强化学习 (Reinforcement Learning, RL) 方法在各类视频游戏中表现出色 [20],但与人类玩家相比仍存在显著效率差距,即使解决最简单的 Atari 游戏也需要数百万次动作输入。当前大量研究聚焦于提升强化学习算法的样本效率 [16][31],但常被忽视的另一个核心问题是:强化学习智能体以"白板"状态处理每个任务,而人类则具备从物理规律到语义认知的丰富先验知识。

Consider the following motivating example: you are tasked with playing an unfamiliar computer game shown in Fig

考虑以下激励性示例:你需要玩一款不熟悉的电脑游戏,如图

Now consider a second scenario in which this same game is re-rendered with new textures, getting rid of semantic and affordance (Gibson, 2014) cues, as shown in Figure 1(b). How would human performance change? We recruited another forty subjects to play this game and found that, on average, it took the players more than twice the time (2 minutes) and action inputs ( 6500) to complete the game. The second game is clearly much harder for humans, likely because it is now more difficult to guess the game structure and goal, as well as to spot obstacles.

现在考虑第二种场景:同一款游戏更换新纹理重新渲染,移除了语义和可供性 (affordance) (Gibson, 2014) 线索,如图 1(b) 所示。人类表现会发生什么变化?我们招募了另外四十名受试者进行游戏测试,发现玩家平均需要耗费两倍以上的时间(2分钟)和操作输入(6500次)才能通关。显然,第二个游戏对人类而言难度显著提升,这可能是因为现在更难推测游戏结构和目标,以及识别障碍物。

For comparison, we can also examine how modern RL algorithms perform on these games. This is not so simple, as most standard RL approaches expect very dense rewards (e.g. continuously updated game-score (Mnih et al., 2015)), whereas we provide only a terminal reward, to mimic how most humans play video games. In such sparse reward scenarios, standard methods like A3C (Mnih et al., 2016) are too sample-inefficient and were too slow to finish the games. Hence, we used a curiosity-based RL algorithm specifically tailored to sparse-reward settings (Pathak et al., 2017), which was able to solve both games. Unlike humans, RL did not show much difference between the two games, taking about 4 million action inputs to solve each one. This should not be surprising. Since the RL agent did not have any prior knowledge about the world, both these games carried roughly the same amount of information from the perspective of the agent.

为进行比较,我们也可以考察现代强化学习 (RL) 算法在这些游戏中的表现。这并不简单,因为大多数标准强化学习方法需要非常密集的奖励信号 (例如持续更新的游戏分数 [20]),而我们只提供最终奖励以模拟人类玩电子游戏的典型方式。在这种稀疏奖励场景下,A3C [20] 等标准方法样本效率过低,无法在合理时间内通关。因此,我们采用了专为稀疏奖励场景设计的基于好奇心的强化学习算法 [21],该算法成功解决了两个游戏。与人类不同,强化学习在两种游戏间未表现出显著差异,每个游戏约需400万次动作输入才能通关。这一结果并不意外。由于强化学习智能体不具备任何先验世界知识,从智能体视角看,这两个游戏携带的信息量大致相当。

This simple experiment highlights the importance of prior knowledge that humans draw upon to quickly solve tasks given to them, as was also pointed out by several earlier studies (Doshi-Velez & Ghahramani, 2011; Lake et al., 2016; Tsividis et al., 2017; Wasser, 2010). Developmental psy- chologists have also been investigating the prior knowledge that children draw upon in learning about the world (Carey, 2009; Spelke & Kinzler, 2007). However, these studies have not explicitly quantified the relative importance of the various priors for problem-solving. Some studies have looked into incorporating priors in RL agents via object representations (Diuk et al., 2008; Kansky et al., 2017) or language grounding (Narasimhan et al., 2017), but progress will be constrained until the field develops a better understanding of the kinds of prior knowledge humans employ.

这个简单的实验凸显了人类在快速解决给定任务时所依赖的先验知识的重要性,正如早期多项研究指出的那样 (Doshi-Velez & Ghahramani, 2011; Lake et al., 2016; Tsividis et al., 2017; Wasser, 2010)。发展心理学家也在研究儿童认识世界时所运用的先验知识 (Carey, 2009; Spelke & Kinzler, 2007)。然而这些研究并未明确量化各类先验知识对问题解决的相对重要性。部分研究尝试通过物体表征 (Diuk et al., 2008; Kansky et al., 2017) 或语言基础 (Narasimhan et al., 2017) 将先验知识融入强化学习智能体,但该领域要取得进展,仍需更深入理解人类运用的先验知识类型。

In this work, we systematically quantify the importance of different types of priors humans bring to bear while solving one particular kind of problem – video games. We chose video games as the task for our investigation because it is relatively easy to methodically change the game to include or mask different kinds of knowledge and run large-scale human studies. Furthermore, video games, such as ATARI, are a popular choice in the reinforcement learning community. The paper consists of a series of ablation studies on a specially-designed game environment, systematically masking out various types of visual information that could be used by humans as priors. The full game (unlike the motivating example above) was designed to be sufficiently complex and difficult for humans to easily measure changes in performance between different testing conditions.

在这项工作中,我们系统地量化了人类在解决特定类型问题(电子游戏)时所运用的不同先验知识的重要性。选择电子游戏作为研究任务,是因为通过系统性地修改游戏内容来包含或屏蔽各类知识,并开展大规模人类研究相对容易。此外,ATARI等电子游戏是强化学习领域的常用测试平台。本文通过在一款专门设计的游戏环境中进行系列消融实验,系统性地屏蔽人类可能用作先验的不同视觉信息类型。与前述示例不同,完整游戏被设计得足够复杂困难,以便准确测量人类在不同测试条件下的表现差异。

We find that removal of some prior knowledge causes a drastic degradation in the performance of human players from 2 minutes to over 20 minutes. Another key finding of our work is that while specific knowledge, such as “ladders are to be climbed”, “keys are used to open doors”, “jumping on spikes is dangerous”, is important for humans to quickly solve games, more general priors about the importance of objects and visual consistency are even more critical.

我们发现,移除某些先验知识会导致人类玩家的表现急剧下降,从2分钟延长至超过20分钟。另一个关键发现是,虽然具体知识(如"梯子用于攀爬"、"钥匙用于开门"、"踩到尖刺很危险")对人类快速通关很重要,但关于物体重要性和视觉一致性的更普遍先验知识更为关键。

2. Method

2. 方法

To investigate the aspects of visual information that enable humans to efficiently solve video games, we designed a browser-based platform game consisting of an agent sprite, platforms, ladders, angry pink object that kills the agent, spikes that are dangerous to jump on, a key, and a door (see Figure 2 (a)). The agent sprite can be moved with the help of arrow keys. A terminal reward of $+1$ is provided when the agent reaches the door after having to taken the key, thereby terminating the game. The game is reset whenever the agent touches the enemy, jumps on the spike, or falls below the lowest platform. We made this game to resemble the exploration problems faced in the classic ATARI game of Montezuma’s Revenge that has proven to be very challenging for deep reinforcement learning techniques (Bellemare et al., 2016; Mnih et al., 2015). Unlike the motivating example, this game is too large-scale to be solved by RL agents, but provides the complexity we need to run a wide range of human experiments.

为探究人类高效解决电子游戏所需的视觉信息要素,我们设计了一款基于浏览器的平台游戏。游戏包含智能体精灵、平台、梯子、会杀死智能体的粉色敌对物体、跳跃危险的尖刺、钥匙和门(见图2(a))。玩家可通过方向键操控智能体精灵。当智能体取得钥匙后抵达门处时,将获得终止奖励$+1$并结束游戏。若智能体接触敌人、跳上尖刺或坠落至最底层平台下方,游戏将重置。该游戏模拟了经典ATARI游戏《蒙特祖马的复仇》中的探索难题——该游戏已被证明对深度强化学习技术极具挑战性(Bellemare et al., 2016; Mnih et al., 2015)。与启发案例不同,本游戏规模过大而难以被强化学习智能体攻克,但恰好提供了开展多样化人类实验所需的复杂度。

We created different versions of the video game by rerendering various entities such as ladders, enemies, keys, platforms etc. using alternate textures (Figure 2). These textures were chosen to mask various forms of prior knowledge that are described in the experiments section. We also changed various physical properties of the game, such as the effect of gravity, and the way the agent interacts with its environment. Note that all the games were exactly the same in their underlying structure and reward, as well as the shortest path to reach the goal, thereby ensuring that the change in human performance (if any) is only due to masking of the priors.

我们通过使用替代纹理重新渲染梯子、敌人、钥匙、平台等各种实体,创建了不同版本的游戏(图2)。选择这些纹理是为了掩盖实验部分描述的各种形式的先验知识。我们还改变了游戏的各种物理属性,例如重力效果,以及智能体与环境交互的方式。需要注意的是,所有游戏在底层结构、奖励以及到达目标的最短路径方面完全相同,从而确保人类表现的任何变化(如果有)仅是由于先验知识的掩盖所致。

We quantified human performance on each version of the game by recruiting 120 participants from Amazon Mechanical Turk. Each participant was instructed to finish the game as quickly as possible using the arrow keys as controls, but no information about the goals or the reward structure of the game was communicated. Each participant was paid $1 for successfully completing the game. The maximum time allowed for playing the game was set to 30 minutes. For each participant, we recorded the (x,y) position of the player at every step of the game, the total time taken by the participant to finish the game and the total number of deaths before finishing the game. We used this data to quantify the performance of each participant. Note that each participant was only allowed to complete a game once, and could not participate again (i.e. different 120 participants played each version of the game).

我们通过从Amazon Mechanical Turk招募120名参与者,量化了人类在游戏每个版本上的表现。每位参与者被要求仅使用方向键作为控制,尽快完成游戏,但未被告知游戏目标或奖励结构的相关信息。成功完成游戏的参与者可获得1美元报酬,单次游戏最长允许时长为30分钟。对于每位参与者,我们记录了游戏过程中每一步玩家的(x,y)坐标位置、完成游戏的总耗时以及通关前的总死亡次数,并以此量化其表现。需注意的是,每位参与者仅能完成一次游戏且不可重复参与(即不同版本的游戏由不同的120名参与者体验)。

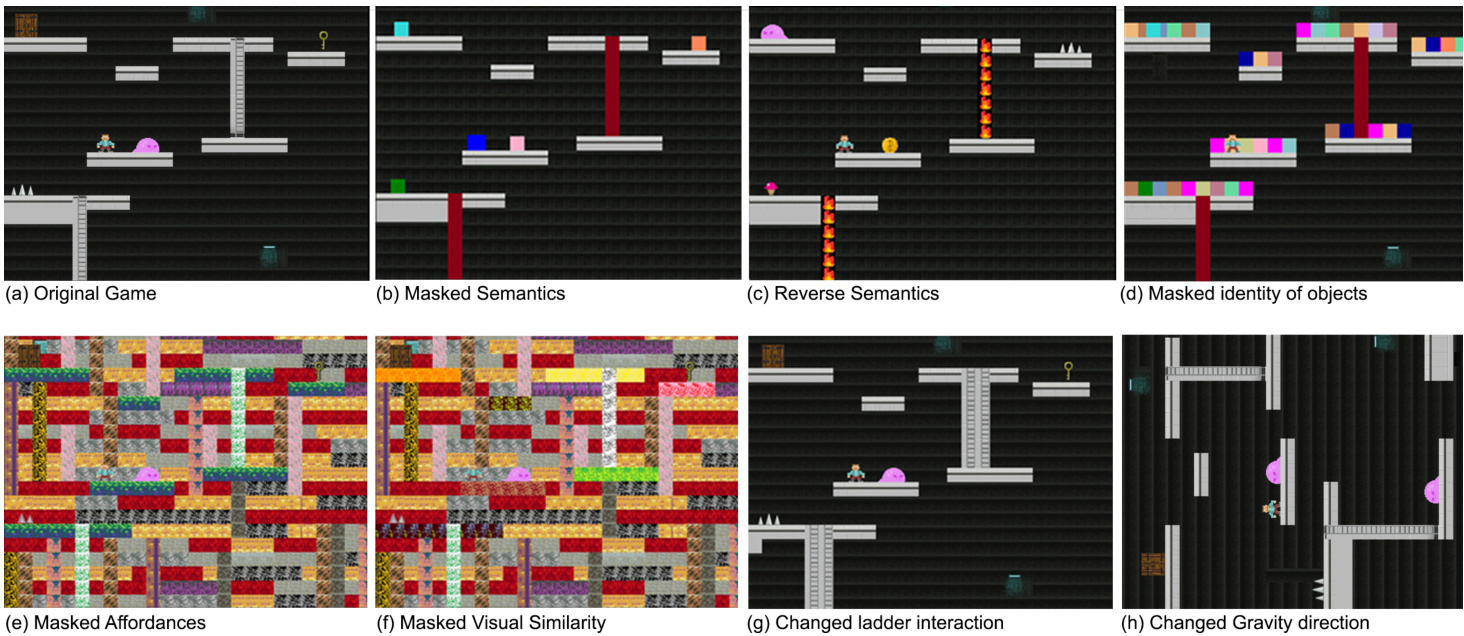

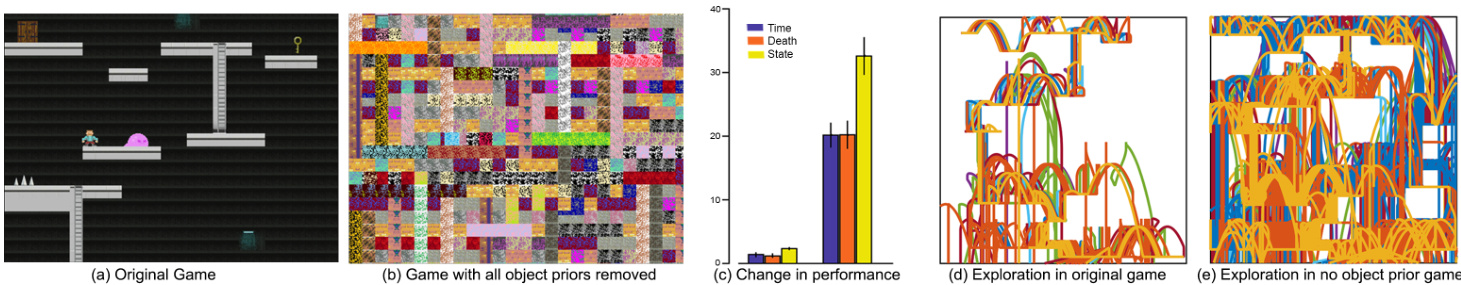

Figure 2. Various game manipulations. (a) Original version of the game. (b) Game with masked objects to ablate semantics prior. (c) Game with reversed associations as an alternate way to ablate semantics prior. (d) Game with masked objects and distractor objects to ablate the concept of object. (e) Game with background textures to ablate affordance prior. (f) Game with background textures and different colors for all platforms to ablate similarity prior. (g) Game with modified ladder to hinder participant’s prior about ladder interactions. (h) Rotated game to change participant’s prior about gravity. Readers are encouraged to play all these games online2.

图 2: 多种游戏操控方式。(a) 游戏原始版本。(b) 通过遮挡物体消除语义先验的游戏版本。(c) 通过反转关联关系消除语义先验的替代方案。(d) 通过遮挡物体并添加干扰物消除物体概念的游戏版本。(e) 通过添加背景纹理消除功能可供性先验的游戏版本。(f) 通过添加背景纹理并为所有平台设置不同颜色消除相似性先验的游戏版本。(g) 通过修改梯子结构阻碍参与者对梯子交互先验认知的游戏版本。(h) 通过旋转游戏画面改变参与者重力先验认知的游戏版本。建议读者在线体验所有这些游戏版本2。

3. Quantifying the importance of object priors

3. 量化物体先验的重要性

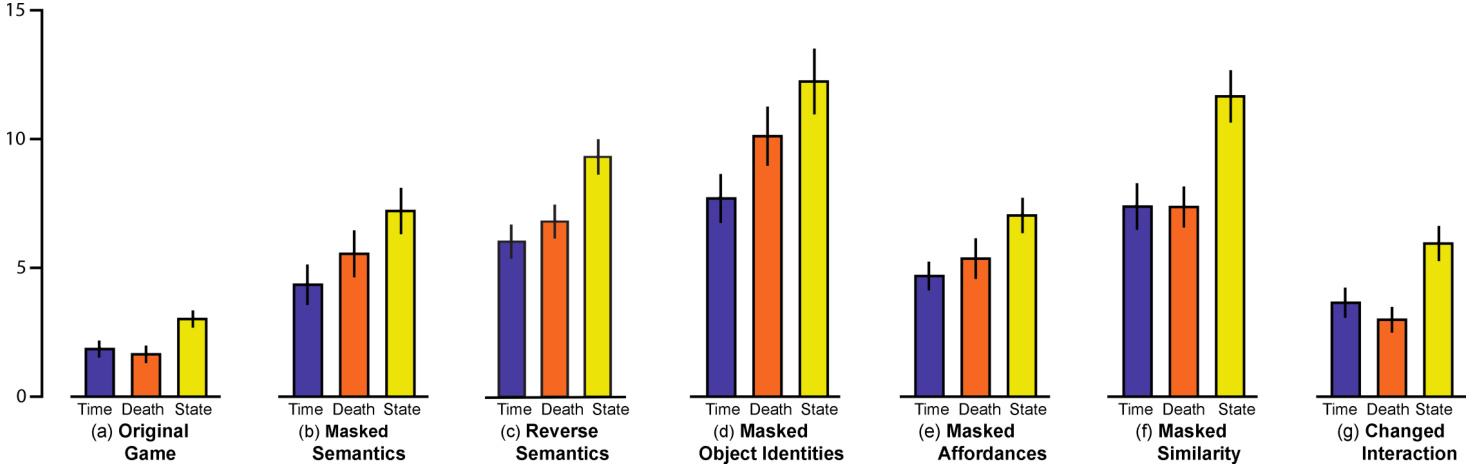

The original game (available to play at this link) is shown in Figure 2(a). A single glance at this game is enough to inform human players that the agent sprite has to reach the key to open the door while avoiding the dangerous objects like spikes and angry pink slime. Un surprisingly, humans quickly solve this game. Figure 3(a) shows that the average time taken to complete the game is 1.8 minutes (blue bar) and the average number of deaths (3.3, orange bar) and unique game states visited (3011, yellow bar) are all quite small.

原版游戏(可在此链接游玩)如图 2(a)所示。人类玩家只需瞥一眼就能明白:智能体精灵需要拿到钥匙开门,同时避开尖刺和愤怒粉色粘液等危险物体。不出所料,人类能快速通关该游戏。图 3(a)显示平均通关时间为1.8分钟(蓝色柱)、平均死亡次数(3.3次,橙色柱)和访问的唯一游戏状态数(3011次,黄色柱)都处于较低水平。

3.1. Semantics

3.1. 语义

To study the importance of prior knowledge about object semantics, we rendered objects and ladders with blocks of uniform color as shown in Figure 2(b). This game can be played at this link. In this version, the visual appearance of objects conveys no information about their semantics. Results in Figure 3(b) show that human players take more than twice the time (4.3 minutes), have higher number of deaths (11.1), and explore significantly larger number of states (7205) as compared to the original game (p-value: $p<0.01,$ ). This clearly demonstrates that masking semantics hurts human performance.

为了研究关于物体语义的先验知识的重要性,我们用纯色方块渲染了物体和梯子,如图2(b)所示。该游戏可通过此链接体验。在此版本中,物体的视觉外观不传递任何语义信息。图3(b)结果显示,与原版游戏相比,人类玩家的通关时间延长了一倍以上(4.3分钟)、死亡次数更高(11.1次)、探索的状态数量显著增加(7205个)(p值: $p<0.01,$ )。这清楚地表明,遮蔽语义信息会损害人类玩家的表现。

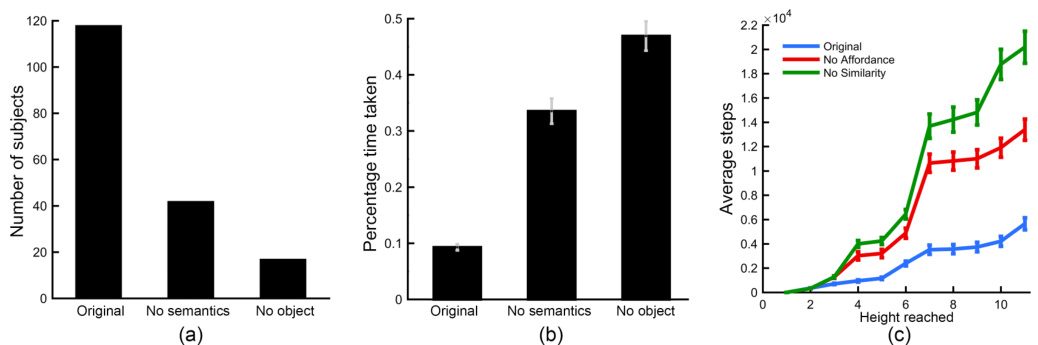

A natural question is how do humans make use of semantic information? One hypothesis is that knowledge of semantics enables humans to infer the latent reward structure of the game. If this indeed is the case, then in the original game, where the key and the door are both visible, players should first visit the key and then go to the door, while in the version of the game without semantics, players should not exhibit such bias. We found that in the original game, nearly all participants reached the key first, while in the version with masked semantics only 42 out of 120 participants reached the key before the door (see Figure 4(a)). Moreover, human players took significantly longer to reach the door after taking the key as compared to the original game (see Figure 4(b)). This result provides further evidence that in the absence of semantics, humans are unable to infer the reward structure and consequently significantly increase their exploration. To rule out the possibility that increase in time is simply due to the fact players take longer to finish the game without semantics, the time to reach the door after taking the key was normalized by the total amount of time spent by the player to complete the game.

一个自然的问题是,人类如何利用语义信息?一种假设是,对语义的认知使人类能够推断游戏的潜在奖励结构。如果确实如此,那么在原始游戏中,当钥匙和门都可见时,玩家应该先拿到钥匙再去门那里;而在没有语义的版本中,玩家则不应表现出这种倾向。我们发现,在原始游戏中,几乎所有参与者都先拿到了钥匙,而在语义被遮蔽的版本中,120名参与者中只有42人在到达门前先拿到了钥匙(见图4(a))。此外,与原始游戏相比,人类玩家在拿到钥匙后到达门的时间显著延长(见图4(b))。这一结果进一步证明,在没有语义的情况下,人类无法推断奖励结构,因此显著增加了探索行为。为了排除时间增加仅仅是因为玩家在没有语义的情况下完成游戏耗时更长的可能性,拿到钥匙后到达门的时间已按玩家完成游戏的总时间进行了标准化处理。

To further quantify the importance of semantics, instead of simply masking, we manipulated the semantic prior by swapping the semantics between different entities. As seen on Figure 4(c), we replaced the pink enemy and spikes by coins and ice-cream objects respectively which have a positive connotation; the ladder by fire, the key and the door by spikes and enemies which have negative connotations (see game link). As shown in Figure 3(c), the participants took longer to solve this game (6.1 minutes, $p<0.01,$ ). The average number of deaths (13.7) was also significantly more and the participants explored more states (9400) compared to the original version $\mathit{f p}<0.01$ for both). Interestingly, the participants also took longer compared to the masked semantics version $\phantom{0}p<0.05\phantom{0}$ implying that when we reverse semantic information, humans find the game even tougher.

为了进一步量化语义的重要性,我们没有简单地屏蔽信息,而是通过在不同实体间交换语义来操控语义先验。如图4(c)所示,我们将粉色敌人和尖刺分别替换为具有积极含义的金币和冰淇淋物体;将梯子替换为火焰,钥匙和门替换为具有负面含义的尖刺和敌人(参见游戏链接)。如图3(c)所示,参与者解决这个游戏花费了更长时间(6.1分钟,$p<0.01$)。与原版相比,平均死亡次数(13.7次)显著增加,参与者探索了更多状态(9400次)(两者均$\mathit{f p}<0.01$)。有趣的是,与屏蔽语义版本相比,参与者花费的时间也更长($p<0.05$),这意味着当我们反转语义信息时,人类会觉得游戏更加困难。

Figure 3. Quantifying the influence of various object priors. The blue bar shows average time taken by humans (in minutes), orange bar shows the average number of deaths, and yellow bar shows the number of unique states visited by players to solve the various games. For visualization purposes, the number of deaths is divided by 2, and the number of states is divided by 1000 respectively.

图 3: 量化不同物体先验的影响。蓝色柱状图显示人类完成游戏的平均耗时(单位:分钟),橙色柱状图显示平均死亡次数,黄色柱状图显示玩家为通关所探索的独特状态数量。为便于可视化展示,死亡次数数据除以2,状态数量数据除以1000。

3.2. Objects as Sub-goals for Exploration

3.2. 将对象作为探索的子目标

While blocks of uniform color in the game shown in Figure 2(b) convey no semantics, they are distinct from the background and seem to attract human attention. It is possible that humans infer these distinct entities (or objects) as sub-goals, which results in more efficient exploration than random search. That is, there is something special about objects that draws human attention compared to any random piece of texture. To test this, we modified the game to cover each space on the platform with a block of different color to hide where the objects are (see Figure 2(d), game link). Most colored blocks are placebos and do not correspond to any object and the actual objects have the same color and form as in the previous version of the game with masked semantics (i.e., Figure 2(b)). If the prior knowledge that visibly distinct entities are interesting to explore is critical, this game manipulation should lead to a significant drop in human performance.

图 2(b) 中游戏展示的纯色色块虽然不传达任何语义,但它们与背景明显不同,似乎能吸引人类注意力。人类可能将这些独特实体(或物体)推断为子目标,从而比随机搜索更高效地进行探索。也就是说,与任意随机纹理相比,物体具有某种吸引人类注意力的特殊属性。为验证这一点,我们修改了游戏设计:用不同颜色的色块覆盖平台每个位置以隐藏物体位置(见图 2(d),游戏链接)。大多数彩色色块是无效的,并不对应任何物体,而实际物体仍保持语义遮蔽版本(即图 2(b))相同的颜色和形态。若"视觉上独特的实体值得探索"这一先验知识确实关键,该游戏改动应会导致人类表现显著下降。

Results in Figure 3(d) show that masking the concept of objects leads to drastic deterioration in performance. The average time taken by human players to solve the game is nearly four times longer (7.7 minutes), the number of deaths is nearly six times greater (20.2), and humans explore four times as many game states (12, 232) as compared to the original game. When compared to the game version in which only semantic information was removed (Figure 3(b)), the time taken, number of deaths and number of states are all significantly greater $(p<0.01)$ . When only semantics are removed, after encountering one object, human players become aware of what possible locations might be interesting to explore next. However, when concept of objects is also masked, it is unclear what to explore next. This effect can be seen by the increase in normalized time taken to reach the door from the key as compared to the game where only semantics are masked (Figure 4(b)). All these results suggest that concept of objects i.e. knowing that visibly distinct entities are interesting and can be used as sub-goals for exploration, is a critical prior and perhaps more important than knowledge of semantics.

图3(d)中的结果表明,遮蔽物体概念会导致性能急剧下降。与原始游戏相比,人类玩家解决游戏的平均耗时延长近四倍(7.7分钟),死亡次数增加近六倍(20.2次),探索的游戏状态数量达到四倍(12,232个)。相较于仅移除语义信息的游戏版本(图3(b)),耗时、死亡次数和状态数量均显著增加$(p<0.01)$。当仅移除语义信息时,人类玩家在接触一个物体后就能意识到下一步值得探索的可能位置;而遮蔽物体概念后,玩家将无法明确后续探索目标。这一效应可通过标准化耗时增幅观察到:相较于仅遮蔽语义的游戏(图4(b)),从钥匙到门的耗时显著增加。所有结果均表明,物体概念(即认知到视觉可区分的实体具有探索价值并可作为子目标)是至关重要的先验知识,其重要性可能超过语义知识。

3.3. Afford ances

3.3. 可供性

Until now, we manipulated objects in ways that made inferring the underlying reward structure of the game non-trivial. However, in these games it was obvious for humans that platforms can support agent sprites, ladders could be climbed to reach different platforms (even when the ladders were colored in uniform red in games shown in Figure 2(b,c), the connectivity pattern revealed where the ladders were) and black parts of the game constitute free space. Here, the platforms and ladders afford the actions of walking and climbing (Gibson, 2014), irrespective of their appearance. In the next set of experiments, we manipulated the game to mask the affordance prior.

到目前为止,我们操控物体的方式使得推断游戏潜在的奖励结构变得不简单。然而,在这些游戏中,对人类而言明显的是:平台可以支撑智能体精灵,梯子可以攀爬以到达不同平台(即使图2(b,c)所示游戏中梯子被统一涂成红色,其连接模式仍揭示了梯子的位置),而游戏的黑色部分构成自由空间。这里,平台和梯子提供了行走和攀爬的动作可能性(Gibson, 2014),与其外观无关。在下一组实验中,我们通过操控游戏来掩盖这种可供性先验。

One way to mask afford ances is to fill free space with random textures, which are visually similar to textures used for rendering ladders and platforms (see Figure 2(e), game link). Note that in this game manipulation, objects and their semantics are clearly observable. When tasked to play this game, as shown in Figure 3(e), humans require significantly more time (4.7 minutes), die more often (10.7), and visit more states (7031) compared to the original game $\left(p<0.01\right)$ . On the other hand, there is no significant difference in performance compared to the game without semantics, i.e., Figure 2(b), implying that the affordance prior is as important as the semantics prior in our setup.

掩盖功能可见性的一种方法是用随机纹理填充空白区域,这些纹理在视觉上与用于渲染梯子和平台的纹理相似(见图2(e),游戏链接)。需要注意的是,在这种游戏操作中,物体及其语义仍然清晰可辨。如图3(e)所示,当人类玩家被要求玩这个版本的游戏时,相比原版游戏$\left(p<0.01\right)$,他们需要明显更多的时间(4.7分钟)、死亡次数更多(10.7次)、经历更多游戏状态(7031个)。另一方面,与无语义版本的游戏(即图2(b))相比,玩家表现并无显著差异,这表明在我们的实验设置中,功能可见性先验与语义先验同等重要。

Figure 4. Change in behavior upon ablation of various priors. (a) Graph comparing number of participants that reached the key before the door in the original version, game without semantics, and game without object prior. (b) Amount of time taken by participants to reach the door once they obtained the key. (c) Average number of steps taken by participants to reach various vertical levels in original version, game without affordance, and game without similarity.

图 4: 消融不同先验条件后的行为变化。(a) 原始版本、无语义游戏和无物体先验游戏中,参与者先拿到钥匙再到达门的数量对比图。(b) 参与者获得钥匙后到达门所花费的时间。(c) 原始版本、无功能可供性游戏和无相似性游戏中,参与者到达不同垂直高度所需的平均步数。

3.4. Things that look similar, behave similarly

3.4. 相似的事物,行为也相似

In the previous game, although we masked affordance information, once the player realizes that it is possible to stand on a particular texture and climb a specific texture, it is easy to use color/texture similarity to identify other platforms and ladders in the game. Similarly, in the game with masked semantics (Figure 2(b)), visual similarity can be used to identify other enemies and spikes. These considerations suggest that a general prior of the form that things that look the same act the same might help humans efficiently explore environments where semantics or afford ances are hidden.

在前一局游戏中,虽然我们隐藏了功能可见性(affordance)信息,但一旦玩家意识到可以站在特定纹理上或攀爬特定纹理,就很容易利用颜色/纹理相似性识别游戏中的其他平台和梯子。同样,在语义被隐藏的游戏中(图2(b)),视觉相似性可用于识别其他敌人和尖刺。这些现象表明,当语义或功能可见性被隐藏时,"看起来相同的事物行为也相同"这种通用先验可能帮助人类高效探索环境。

We tested this hypothesis by modifying the masked affordance game in a way that none of the platforms and ladders had the same visual texture (Figure 2(f), game link). Such rendering prevented human players from using the similarity prior. Figure 3(f)) shows that performance of humans was significantly worse in comparison to the original game (Figure 2(a)), the game with masked semantics (Figure 2(b)) and the game with masked afford ances (Figure 2(e)) $(p<0.01)$ . When compared to the game with no object information (Figure 2(d)), the time to complete the game (7.6 minutes) and the number of states explored by players were similar (11, 715), but the number of deaths (14.8) was significantly lower $(p<0.01)$ . These results suggest that visual similarity is the second most important prior used by humans in gameplay after the knowledge of directing exploration towards objects.

我们通过修改掩蔽可供性游戏来验证这一假设,使所有平台和梯子都不具有相同的视觉纹理 (图 2(f),游戏链接)。这种渲染方式阻止了人类玩家使用相似性先验。图 3(f) 显示,与原始游戏 (图 2(a))、语义掩蔽游戏 (图 2(b)) 和可供性掩蔽游戏 (图 2(e)) 相比,人类表现显著下降 $(p<0.01)$。与无物体信息游戏 (图 2(d)) 相比,游戏完成时间 (7.6 分钟) 和玩家探索的状态数 (11,715) 相近,但死亡次数 (14.8) 显著降低 $(p<0.01)$。这些结果表明,视觉相似性是继引导探索物体知识之后,人类在游戏中使用第二重要的先验。

In order to gain insight into how this prior knowledge affects humans, we investigated the exploration pattern of human players. In the game when all information is visible we expected that the progress of humans would be uniform in time. In the case when afford ances are removed, the human players would initially take some time to figure out what visual pattern corresponds to what entity and then quickly make progress in the game. Finally, in the case when the similarity prior is removed, we would expect human players to be unable to generalize any knowledge across the game and to take large amounts of time exploring the environment even towards the end. We investigated if this indeed was true by computing the time taken by each player to reach different vertical distances in the game for the first time. Note that the door is on the top of the game, so the moving up corresponds to getting closer to solving the game. The results of this analysis are shown in Figure 4(c). The horizontal-axis shows the height reached by the player and the vertical-axis show the average time taken by the players. As the figure shows, the results confirm our hypothesis.

为了探究这种先验知识如何影响人类,我们研究了人类玩家的探索模式。在游戏信息完全可见的情况下,我们预期人类玩家的进度会在时间上保持均匀。当可供性被移除时,人类玩家最初会花些时间弄清哪些视觉模式对应哪些实体,然后迅速取得游戏进展。最后,当相似性先验被移除时,我们预期人类玩家将无法在游戏中泛化任何知识,即使到游戏后期仍需花费大量时间探索环境。我们通过计算每位玩家首次到达游戏中不同垂直高度所需的时间,验证了这一假设是否成立。请注意,出口位于游戏顶部,因此向上移动意味着更接近通关。分析结果如图4(c)所示,横轴表示玩家到达的高度,纵轴显示玩家的平均耗时。如图所示,结果证实了我们的假设。

3.5. How to interact with objects

3.5. 如何与对象交互

Until now we have analyzed the prior knowledge used by humans to interpret the visual structure in the game. However, this interpretation is only useful if the player understands what to do with the interpretation. Humans seem to possess knowledge about how to interact with different objects. For example, monsters can be avoided by jumping over them, ladders can be climbed by pressing the up key repeatedly etc. RL agents do not possess such priors and must learn how to interact with objects by mere trial and error.

截至目前,我们已经分析了人类用于解读游戏中视觉结构的先验知识。然而,只有当玩家理解如何运用这种解读时,它才有意义。人类似乎具备与不同物体互动的知识,例如通过跳跃避开怪物、反复按上键攀爬梯子等。强化学习 (RL) 智能体并不具备此类先验知识,必须通过反复试错来学习如何与物体互动。

As an initial step towards studying the importance of this prior, we created a version of the game in which the ladders couldn’t be climbed by simply pressing the up key. Instead, the ladders were zigzag in nature and in order to climb the ladder players had to press the up key, followed by alternating presses between right and left key. Note that the ladders in this version looked like normal ladders, so players couldn’t infer ladder interaction by simply looking at them (see Figure $2(\mathbf{g})$ , game link). As shown in Figure $3(\mathrm{g})$ , changing ladder interaction increases the time taken (3.6 minutes), number of deaths (6), and states explored (5942) when compared to the original game $(p<0.01)$ .

为了初步研究这一先验知识的重要性,我们创建了一个游戏版本,其中梯子不能仅通过按上键攀爬。相反,梯子呈锯齿状,玩家必须按上键,然后交替按左右键才能攀爬。需要注意的是,该版本中的梯子外观与普通梯子相同,因此玩家无法仅通过观察来推断梯子的交互方式 (参见图 $2(\mathbf{g})$,游戏链接)。如图 $3(\mathrm{g})$ 所示,与原版游戏 $(p<0.01)$ 相比,改变梯子交互方式会增加通关时间 (3.6分钟)、死亡次数 (6次) 和探索的状态数 (5942个)。

Figure 5. Masking all object priors drastically affects human performance. (a) Original game (top) and version without any object priors (bottom). (b) Graph depicting difference in participant’s performance for both the games. (c) Exploration trajectory for original versi